Long before the restaurant, Parisians had far more public food options than is often thought. Starting as early as the thirteenth century, inns, taverns and cabarets sold food that was varied and sometimes even sophisticated. Meanwhile, roasters and pastry cooks not only provided street food, but often supplied private functions. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, one writer complained about diners paying dearly for “salmagundis and other various mishmashes” at favored cabarets. By the mid-seventeenth century, the traiteurs—the cook-caterers— dominated fine food service, but tables d’hote, gargottes and guinguettes also began to provide meals. In 1767, when Mathurin Roze de Chantoiseau opened his “restorer” on the rue des Poulies, Parisians had already long been used to dining out and often doing so well at a series of (in modern terms) trendy places.

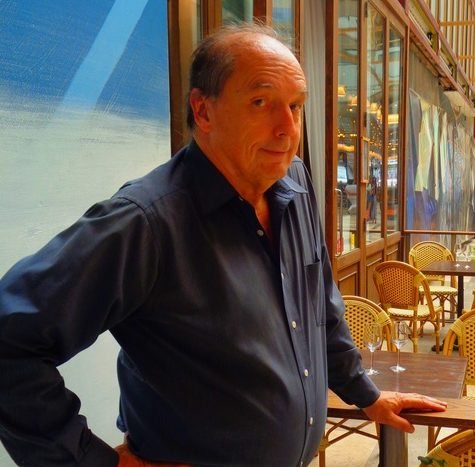

Jim Chevallier’s A History of the Food of Paris: From Roast Mammoth to Steak Frites is part of the Big City Food Biographies book series. He is largely a bread historian and his work on the baguette and the croissant has been cited in both books and periodicals; his latest book is Before the Baguette: The History of French Bread. As a bread historian, he has contributed to the Dictionnaire Universel du Pain, the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America (2nd edition) and Modernist Bread; he is also a contributor to “Savoring Gotham.” Aside from continuing research into Parisian food and French bread history, he is working on a book about early medieval French food.